Until recently my understanding of separated migrant children was largely shaped by ongoing media coverage, which has powerfully portrayed the treacherous and traumatic journeys that many children experience to reach the UK.

Having now worked alongside childrens services commissioners and education colleagues, and listened to social workers and personal advisors who work with separated migrant children directly, I have gained a profound understanding of the everyday challenges these children encounter, and the complexity of providing much needed support to separated migrant children. This experience has had a more significant impact than merely increasing my understanding of an issue, it has reshaped my entire approach to how I start a piece of analytical work.

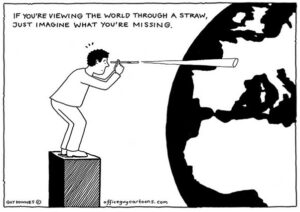

As an Analyst, previously when I started an analytical project, I researched the new topic, put together a literature review, and discussed the research questions with the customer, ensuring I had a very good understanding of the issue I was analysing. And while I always understood these to be the right steps at the beginning of the project lifecycle, and went through them whenever new work came my way, the experience I had of listening to the range of professionals supporting separated migrant children (who knew children’s services inside and out), and therefore immersing myself in the topic, and allowing myself to be educated by being brave enough to ask ‘silly’ questions, enabled me to realise that, while I may have previously understood the main analytical questions down to a T, I often did not go far enough in understanding the research question in the larger landscape of everything else that was going on.

When I was then tasked with looking into the feasibility of forecasting this cohort of young people, this recognition pushed me to research the topic to an extent I hadn’t done before. I read through article after article on developments happening in Essex and in other local authorities, and through materials outlining their potential implications, looked at changes in national migration law and what they meant for service users, and spoke to team managers and service delivery leads, as well as to other analysts with children’s data experience. I wanted to know what else was going on at a national and local level that could impact our model.

With my new research approach, I realised that while I was aware of a lot of the factors impacting services and therefore the children they support, I had not considered the extent of the ramifications or understood them to this degree before. It also helped me understand some of the ways in which all these factors impact each other, generating a complex set of conditions within which the service needs to operate, often meaning decision-making and future planning can be challenging.

Widening the context and methods of my research to include interviews with area experts, assessments from external agencies, central government reports, case studies, media articles, internal dashboards, and much more, and having conversations with different professionals within the service, as well as other data professionals, allowed me to create an overview of everything we may need to consider when producing future analysis for the services supporting separated migrant children. Feedback on my research and analysis from one of my colleagues perfectly summarised the journey I went through while doing this work, “while I was familiar with a lot of this information, this really helped connect all the dots”.

It's important not to lose sight of proportionality, and naturally our work is driven by the deadlines of decision-making. However, what i've learned is when to recognise the value of going beyond researching my key questions, then taking a step back and looking at the whole picture, to enable myself to connect all the dots.

Forecasting is always tricky, and without this in-depth understanding of all the factors I would have found it difficult to feel confident choosing an approach to forecasting this cohort. Exploring all forecasting options with the bigger picture in mind allowed me to understand which analytical approaches would provide the best possible outputs for the service, and what the limitations were. Assessing the ethical risks of different forecasting methods was made possible by this research approach, as it helped me understand the potential implications for the service across the different options I was exploring. Finally, it provided me with a new level of confidence when building recommendations for the service. I am sure that many more stages in the lifecycle of a project, from understanding trends in data to interpreting findings, will be made easier as I continue to look at the bigger picture as opposed to ‘through a straw’!