Volatile energy markets. Fuel poverty crisis. The headlines are grim:

- Global shortage of gas has forced an increase on the price cap on energy bills

- Households will see costs increase by an estimated 52%

- UK and European sanctions will ban imports of Russian oil exacerbating energy market conditions

- Future government policy aimed at climate change mitigation could further increase energy prices for households.

We know from our recent work on the financial vulnerability of our residents that income levels, the cost of living and COVID are all already contributing to the challenges our residents are facing here in Essex. And we know that around 7% of households in Essex use fuel alternatives to grid/mains energy, sources that are not protected by the cap. Consequently, they are exposed to the instability of the energy markets.

We urgently needed the headlines for Essex, to understand which communities were at greater risk of fuel poverty, and how the energy price rises would affect them over the next year so that we can target support to those most in need.

Our rapid response

Teamwork was vital to this project, given the speed required to allow stakeholders to quickly pivot policy responses to provide targeted support. We swiftly identified several methodological approaches, evaluated their pros and cons, and agreed the best course of action. As such, we built upon previous experience of using EPC data to form the basis of our work. By allocating tasks according to our experience and capabilities, we were able to efficiently sift through potential data rapidly bringing the project to life.

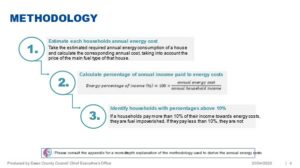

To determine how changes in fuel prices would affect Essex residents, first we needed to select a measure of fuel poverty. Central government identifies a household as being in fuel poverty by whether their dwelling has an EPC rating of D or below, and if their after-housing and energy cost incomes are below the official poverty line.

Due to data constraints, we opted for a more traditional measure: whether a household was spending more than 10% of income on energy bills.

Using data on household incomes and estimated annual energy bills based on energy prices from early 2022, we could identify which households were in fuel poverty before the price cap uplift. To understand how the rising fuel bills might impact households, we simulated the impact of different energy price increases on households’ annual energy bills.

And the data told us…

Our findings identified three main cohorts of interest:

- Older single-person households with limited pension income

- Urban social renters

- Older residents enjoying comfortable retirement

The first cohort we identified were older single-person households with very low pension incomes. These households tend to live in low-value properties that they own outright or in social rented accommodation. Prior to the April 2022 price cap rise, we estimate that 74% of these households were in fuel poverty, rising to 93% following a 52% price increase. The data suggests that 83% of social renters fall within this cohort, providing some insight into our finding that 20% of social renters were likely to be in fuel poverty before the price cap increase. This compares to 5% of private renters and owner-occupiers respectively. Following a 52% energy price increase, we expect to see 30% of social renters in fuel poverty, compared to 24% of private renters and 26% of owner-occupiers. Whilst social renters tend not to spend so much on energy, with an average spend of £996 before the cap rise compared to £1,484 across all cohorts, they are more likely to have lower household incomes to spend in the first place. We also found that social housing tends to receive higher EPC ratings than other tenure types, suggesting that they are more energy efficient. This, coupled with small household sizes goes some way to explain the lower cost of energy within social rented accommodation.

A similar picture can also be seen in the second cohort of interest, urban social renters. Just shy of three quarters of this cohort are social renters and overall, they have a median household income of £14,800. This is considerably lower than across all cohorts, with a median income of £33,100. These households are likely to be situated within urban areas and may be younger than the first cohort. Prior to the price cap rise, we estimate that 17% of this cohort was likely in fuel poverty, rising to 45% following a 52% price rise.

The third cohort, older residents enjoying a comfortable retirement, describes households that tend to receive good pension incomes and usually have some financial assets. Whilst they tend to be single-person households, some may be married couples, and predominantly live in mid-range bungalows or semi-detached houses. We estimated that 14% of this cohort was likely to be in fuel poverty before the 52% price cap rise, with 45% estimated to be in fuel poverty after this increased. This could potentially be due to the fact that these households tend to live in properties with lower-than-average EPC ratings, suggesting that they have lower energy efficiency than other Essex dwellings. Nonetheless, this cohort tends to have more savings than the first two identified, providing something of a safety net.

Across the county, Tendring, Maldon, and Harlow saw over 10% of their households in fuel poverty prior to the OFGEM price cap rise. This increases to all districts except Brentwood and Epping Forest following the 52% price cap increase. This is most stark in Tendring, with 15% of households likely to be in fuel poverty before the price cap rise and 33% following a 52% price increase.

Before and after the 52% price cap rise: Percentage of households in each district likely to be in fuel poverty

Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2021 Contains Royal Mail data © Royal Mail Copyright and database right 2021 Essex County Council: Licence No: 100019602

What next?

This is the starting point of our fuel poverty work, we are working with key stakeholders in areas covering retrofit, housing, families, sustainable growth and climate to agree the next phases of insight to inform campaigns, retrofit programmes, policy decisions and ultimately provide direct support to residents in need.